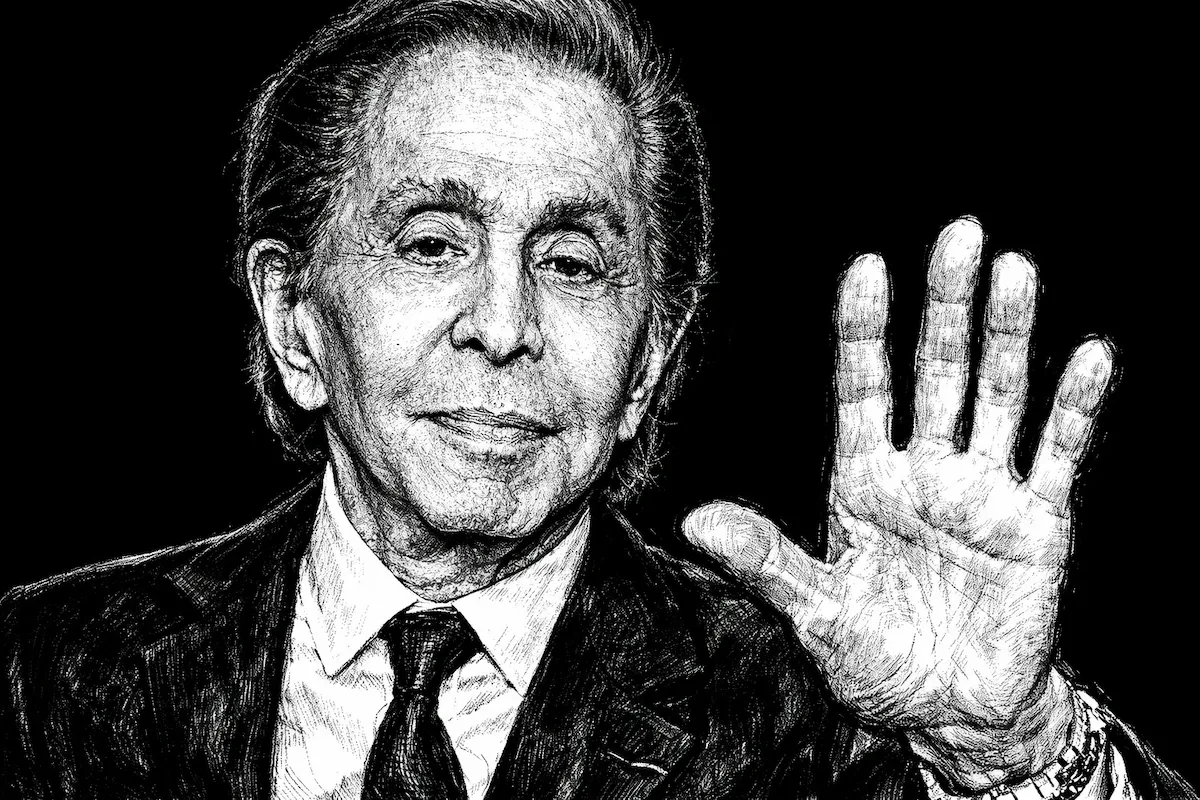

The Roman sun set differently on Monday because the man who spent fifty years painting the city in his signature shade of crimson is gone. Valentino Garavani, died at 93 in the same Roman residence where he cultivated a life of unparalleled splendor. He lived long enough to become a historical monument himself, outlasting the trends that attempted to dismantle the formal elegance he worshiped. His passing marks the end of an era when designers could reign like monarchs, surrounded by courts of pugs, private jets, and beauty that refused to apologize for its cost.

From provincial Italy to Hollywood dreams: Valentino’s early obsession with glamour

Voghera, a small town near Milan, was far from the flash of cameras that would eventually follow Valentino everywhere. He was born there in 1932, the son of bourgeois parents who seemed to have destined him for a life of quiet stability. His parents, Mauro and Teresa, watched as their son displayed an early and almost peculiar affinity for the finer things. He didn’t want standard clothing; he wanted his sweaters made to order so he could control the patterns. He replaced the buttons on his blazers because the factory options did not meet his growing aesthetic standards.

The defining moment of his youth arrived in a darkened movie theater in 1941. The film was Ziegfeld Girl, a Hollywood musical presenting a world of extreme sophistication and decorative excess that fundamentally altered his trajectory. He saw Judy Garland and Lana Turner draped in costumes that functioned as armor for the beautiful. At seventeen, he told his parents he was leaving for Paris. It was a shocking declaration for a family that viewed the French capital as a place of moral danger.

Paris, couture discipline and the birth of Valentino red

In 1950, Paris was the center of the fashion universe. Valentino arrived on the Feast of the Epiphany to begin his education at the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. There, he learned the technical rigors of the craft from a former Dior head seamstress, absorbing the structural secrets that allow a garment to hold its shape. He began his professional career at the house of Jean Dessès, working as an illustrator. Dessès was famous for dressing royalty, which provided Valentino with an early look at the interaction between power and fabric.

After a stint with Guy Laroche, he returned to Italy in 1959. With financial support from his father, he opened his first salon on Via Condotti in Rome. It was during this period that he encountered the color that would define his legacy. While attending an opera in Barcelona, he was struck by the sight of women in the audience wearing various shades of red. They stood out against the darkness of the theater with a vibrancy he decided to capture. Red became his lucky charm, his logo, and the standard conclusion to his runway shows.

Giancarlo Giammetti: the strategic mind behind Valentino’s empire

Valentino was a creator of beauty, but not a businessman. In 1960, a chance meeting at a bar on Via Veneto changed the course of fashion history. He met Giancarlo Giammetti, an architecture student with a sharp mind for logistics and strategy. Giammetti eventually abandoned his studies to join Valentino, forming a partnership that would last over six decades. While Valentino focused on details like the placement of a ruffle or the curve of a seam, Giammetti built the infrastructure of a global brand.

They were lovers for a time, but their bond transcended romance. They became a singular unit, traveling the world together. They were tanned to the same deep mahogany shade and dressed in perfectly tailored suits. Giammetti acted as a protective barrier, enabling Valentino to inhabit a curated world where perfection was the only acceptable standard. This environment was necessary for Valentino’s creativity. He could not function in a messy or unkempt world.

How Valentino dressed power, fame and modern royalty

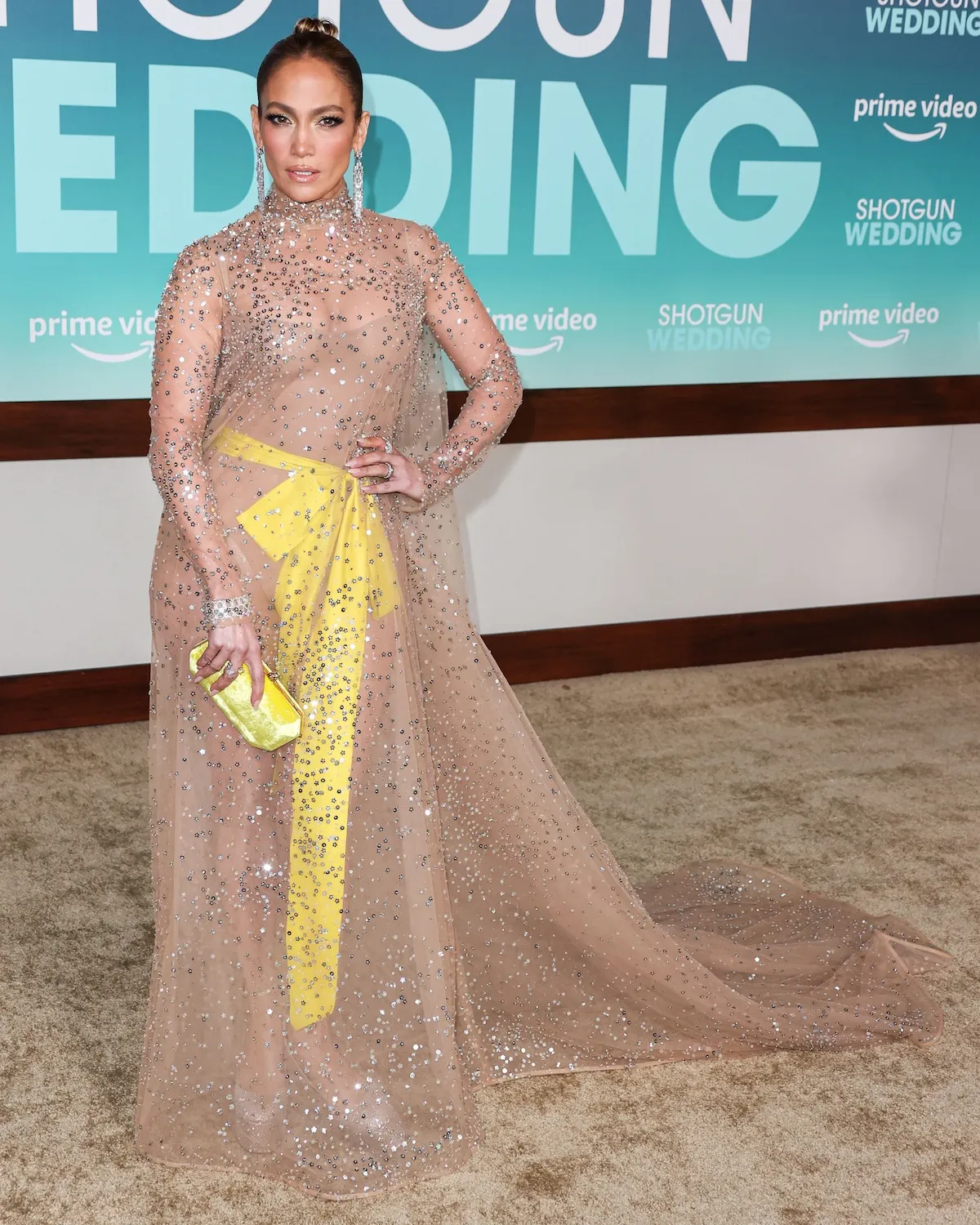

The 1960s saw Valentino rise to international prominence, largely due to the patronage of the world’s most famous women. Jacqueline Kennedy became a client in 1964, and Valentino eventually designed the white lace dress she wore for her wedding to Aristotle Onassis. Elizabeth Taylor was another early supporter, wearing his designs to film premieres and high-society gatherings. His client list included influential figures such as Marella Agnelli and Babe Paley.

Valentino was not concerned with being on the cutting edge of art. He wanted to make women look sensational, a goal he achieved through discipline rather than torture. He rejected the grunge and minimalism of the 1990s, refusing to acknowledge a movement that celebrated the unpolished. To him, fashion was a tool for transformation. He provided the gowns for Julia Roberts and Cate Blanchett when they won their Oscars, proving that his vision of glamour remained relevant even as the industry shifted toward more casual standards.

Follow all the latest news from Fashionotography on Flipboard, or receive it directly in your inbox with Feeder.

From independent house to luxury conglomerates: Valentino’s exit

The late 1990s brought a shift in the way fashion houses operated. Independent brands found it difficult to compete with rising luxury conglomerates. In 1998, Valentino and Giammetti sold their company to HdP for approximately $300 million. This sale initiated a series of ownership changes, ultimately leading to the brand’s acquisition by private equity firms.

Valentino remained the creative lead during these transitions but became increasingly disillusioned with a system that prioritized money and management over design. In 2007, he chose to exit the stage with a massive three-day celebration in Rome. The event featured a runway show near the Vatican and a dinner at the Temple of Venus. The Colosseum was illuminated in Valentino’s signature colors for the occasion. It was a fitting farewell for a man who had been called the last emperor of fashion.

Valentino Red: The birth of a fashion icon

Garavani discovered his signature color by accident. Early in his career, he attended the premiere of Carmen in Barcelona and noticed that women wearing red stood out in the crowd. From 1959 onward, he ended every collection with a red gown. The color became synonymous with his name, serving as a visual shorthand for his particular brand of glamour. Garavani called it a nonfading mark, a logo, and an iconic element.

His design philosophy remained remarkably consistent across decades. He relentlessly pursued beauty and refused to apologize for it. When minimalism and grunge dominated the 1990s, he dismissed both movements. He couldn’t see the appeal of making women look or feel uncomfortable. Fashion critics accused him of ignoring modern complications and refusing to acknowledge changing social dynamics. He didn’t particularly care. His job, he said, was to make women look sensational.

From couture house to global luxury brand

The business grew steadily throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In 1975, Garavani moved his ready-to-wear shows to Paris. He launched his first perfume in 1978. By the following year, his name appeared on licenses for bags, luggage, umbrellas, and handkerchiefs. In Japan, it appeared on cigarette lighters and pens as well. At its peak, the company held approximately 42 licenses. The Italian Olympic team wore Valentino at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

However, by 1998, the landscape had shifted. Massive luxury conglomerates like LVMH and Gucci Group made it nearly impossible for independent designers to compete. Garavani and Giammetti sold their company to HdP, a Fiat-controlled conglomerate, for approximately $300 million. This began a period of ownership changes. In 2002, HdP sold to the Marzotto textile company. In 2005, Marzotto spun off its fashion assets into Valentino Fashion Group. Shortly after, private equity firm Permira acquired the company.

A life after fashion: Palaces, art and absolute control

After stepping away from his brand, Valentino did not retreat into obscurity. He continued to live a life of extreme comfort across his five residences in London, Rome, New York, Gstaad, and Paris. His favorite residence was the Château de Wideville, a seventeenth-century estate that was once owned by the mistress of Louis XIV. Valentino spent years restoring the property and ensuring that the gardens were perfectly manicured and the interiors were filled with his vast collection of Meissen china and Chinese porcelain.

He spent his final years focusing on the foundation he and Giammetti established in 2016. The foundation acquired a historic palazzo in Rome known as PM23, which serves as a center for cultural activities. Last May, he was celebrated one last time with an exhibition of fifty red dresses at PM23. Even absent from the runway, he remained a fixture in the public consciousness, a reminder of a time when fashion prioritized beauty above all else.

Rome bids farewell to the last Emperor of fashion

The public may pay their respects to Valentino on Wednesday and Thursday at Piazza Mignanelli 23. He will lie in state in the city that embraced him and provided the backdrop for his greatest successes. His funeral is scheduled for Friday at the Basilica Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri. It is an appropriate setting for a man who never did anything on a small scale.

Since Garavani’s departure, the fashion house has had several creative directors. Initially, Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli took over, followed by Piccioli alone until 2024 and most recently, Alessandro Michele, who was appointed in March 2024. However, the brand’s foundation remains rooted in the vision of a man who believed that beauty was a powerful tool and wore it like a crown.